China’s Unconventional Nationwide CO₂ Emissions Trading System: The Wide-Ranging Impacts of an Implicit Output Subsidy

This paper assesses the overall costs and distributional impacts of China’s planned nationwide emissions trading system for CO2 emissions reductions, a system that will differ from cap and trade and become the largest CO2 trading system in the world.

Overview and Key Findings

China embarked on what promises to be the world’s largest carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions trading system. When fully implemented, this nationwide system will more than double the amount of CO₂ emissions covered worldwide by some form of emissions pricing.

To reduce emissions, China will rely on a tradable performance standard (TPS), a mechanism that differs significantly from cap and trade (C&T), the approach more frequently adopted worldwide.

This paper assesses the cost-effectiveness and distributional consequences of alternative designs of the TPS in the first program phase, in which the policy applies to the power (electricity) sector. We also compare these impacts with those of a comparable C&T system.

Key findings:

- The economy-wide costs reducing emissions under the TPS are higher than those under a comparable C&T program. This reflects the TPS’s implicit subsidy to electricity output, which causes power plants to make relatively less efficient use of reductions in electricity supply as a mechanism for achieving emissions reductions. The implicit subsidy also reduces the ability of allowance trading to lower costs. Under our central case scenario, the overall costs are 47 percent higher than those under a C&T program that achieves the same CO₂ emissions reductions.

- The program costs depend importantly on a key design choice: the number and variation of benchmarks (maximum emissions-output ratios consistent with compliance).

- Because of its implicit output subsidy, the TPS produces smaller increases in electricity prices than C&T. As a result, it would likely lead to less emissions leakage.

- Despite its higher costs than those of C&T, the TPS can generate significant net gains once environmental benefits are counted. If CO₂ emissions reductions are valued at 290 RMB (or about 44 US dollars) per ton, our central case results indicate that the environmental benefits from the TPS would exceed the policy costs by a factor of about 3.

Abstract

China has embarked on what has the potential to become the largest CO₂ emissions trading system in the world. To reduce emissions, the nation will rely on a tradable performance standard (TPS), an emissions pricing mechanism that differs in important ways from the emissions pricing instruments used in other countries, such as cap and trade (C&T) and a carbon tax. We employ matching analytically and numerically solved models of China’s power sector (the first sector to be covered under China’s TPS) to assess, under alternative designs, the cost-effectiveness and distributional implications of the TPS and to compare these impacts with those of a C&T program with the same coverage and stringency.

We find that achieving given aggregate CO₂-reduction targets is significantly more costly under the TPS than under C&T. This reflects several consequences of the TPS’s implicit subsidy to electricity output. The subsidy causes producers to make less efficient use of output-reduction as a way of reducing emissions (indeed, it induces some producers to increase production). It also reduces the extent to which allowance trading can lower costs. And when the TPS employs multiple benchmarks (maximal emission-output ratios consistent with compliance), it distorts the relative contributions of different power plants to emissions reductions. In our central case, the costs of the TPS are about 47 percent higher than under C&T.

Although the TPS has some disadvantages in terms of overall cost, it also has some attractions relative to C&T. Its rate-based structure allows overall policy stringency to adjust automatically to changes in the business cycle, and because the TPS causes smaller increases in electricity prices than C&T, it would likely lead to less emissions leakage. Also, the use of multiple (i.e., varying) benchmarks, while tending to raise aggregate costs, can reduce disparities in the policy’s costs across technology types and regions of the country.

Even with its higher overall costs than C&T, the TPS can generate significant net gains once its environmental benefits are counted. If emissions reductions are valued at 290 RMB (or about 44 US dollars) per ton, our central case results indicate that the environmental benefits from the TPS exceed the policy costs by a factor of about 3.

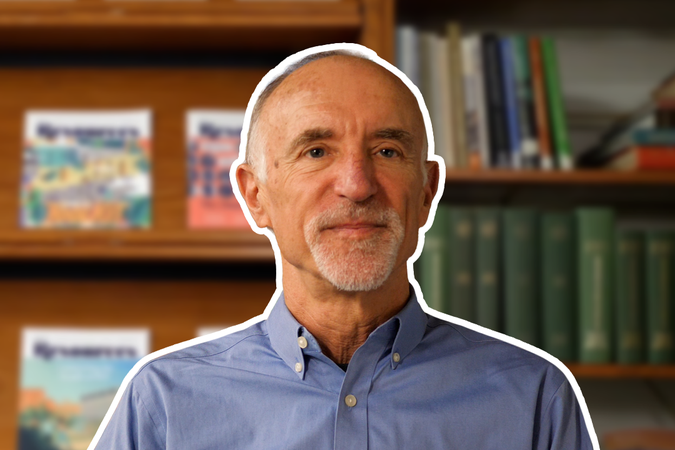

Authors

Xianling Long

Stanford University

Jieyi Lu

Yale University