Reducing Coal Plant Emissions by Cofiring with Natural Gas

The Environmental Protection Agency can rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by cofiring with natural gas at coal plants under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act.

Introduction

Using its existing authority under the Clean Air Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) can jump-start the Biden administration’s plan to reduce US greenhouse gas emissions by 52 percent and contribute important air quality benefits in this decade.

Under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act, the EPA can establish guidelines and require states to develop standards of performance for existing sources of air pollution. These performance standards are emissions limits that the EPA administrator determines are achievable using an adequately demonstrated best system of emissions reductions. This provision has been successfully exercised many times; however, the two times it has been used to regulate carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions at existing electricity-generating units (EGUs), it has failed in the courts. We describe and model an approach that is likely to be more successful, based on the opportunity to use natural gas to cofire with coal to reduce emissions at coal EGUs.

The Obama administration took a broad approach in its Clean Power Plan (CPP), which identified performance standards for the entire power system. This approach was stayed (frozen) by the courts for review based on its breadth, since it identified emissions reductions that were conditioned on actions (such as expanded use of renewable energy) that could be taken at sources other than the regulated existing fossil units. The Trump administration withdrew the CPP before the court’s review was complete and, as a replacement, proposed the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule, which in turn was struck down by the courts because it proposed a standard based on a set of technologies that was too narrow, resulting in emissions reductions that would be insignificant.

We describe a performance standard, based on the opportunity to cofire with natural gas at coal EGUs, that would address most of the concerns that have been raised before the courts. Natural gas cofiring is already a demonstrated and widespread practice. Although the ACE rule explicitly rejected gas cofiring as a basis for a performance standard, previous analysis provided to EPA indicated that in 2017, gas cofiring occurred at 35 percent of coal EGUs across 33 states. Indeed, if the monthly maximum use of gas at these units were achieved in every month, emissions reductions comparable to those anticipated by all other measures in the ACE rule could be achieved. Because a performance standard based on the opportunity for cofiring applies to an individual facility, it does not raise concerns about measures taken outside regulated emissions sources. This approach is based on a broader set of technologies than those included in the ACE rule and is likely to achieve more significant emissions reductions. Importantly, it would provide a soft landing for coal units that choose to phase out production and reduce emissions at units that continue to operate.

We model a natural gas cofiring standard using RFF’s Haiku electricity market model, including gas price forecasts from Annual Energy Outlook 2019, and site-specific estimates of the capital cost to expand gas delivery provided by Natural Resources Defense Council. We identify five key findings.

1. A modest cofiring standard at coal plants can reduce carbon emissions significantly and rapidly.

A cofiring regulation could take three forms. The first form is a plant-specific rate-based standard requiring every plant to reduce its emissions rate to the rate prescribed by the standard. The resulting emissions rate would be identified in state plans and vary by plant, based on the plant’s underlying characteristics and initial heat rate. To comply, a coal plant could cofire with natural gas or install another technology to reach that emissions rate.

The second form is a tradable performance standard that enables a group of coal plants to achieve an average emissions rate equivalent to the standard. In this case, some plants could overcomply by cofiring more than the regulation requires while other plants undercomply. A tradable performance standard could be applied at the state level, or states could be permitted to opt into a national-level tradable performance standard.

The third form is a mass-based standard, which requires that total emissions from a group of coal plants not exceed an emissions budget based on the performance standard’s emissions rate and historical generation.

A mass-based approach was implemented previously under Section 111(d) for nitrogen oxide (NOX) emissions from municipal solid waste facilities and was proposed by EPA but not implemented for mercury emissions from power plants under the Clean Air Mercury Rule. This approach also was used to convert an emissions rate standard for NOX into the mass-based emissions budget trading program. We model a mass-based standard that multiplies generation levels (in MWh) in a previous year by the emissions rate standard (tons/MWh) to arrive at a budget (tons). We describe a one-year and two-year look back at previous generation levels and update the emissions limit each year.

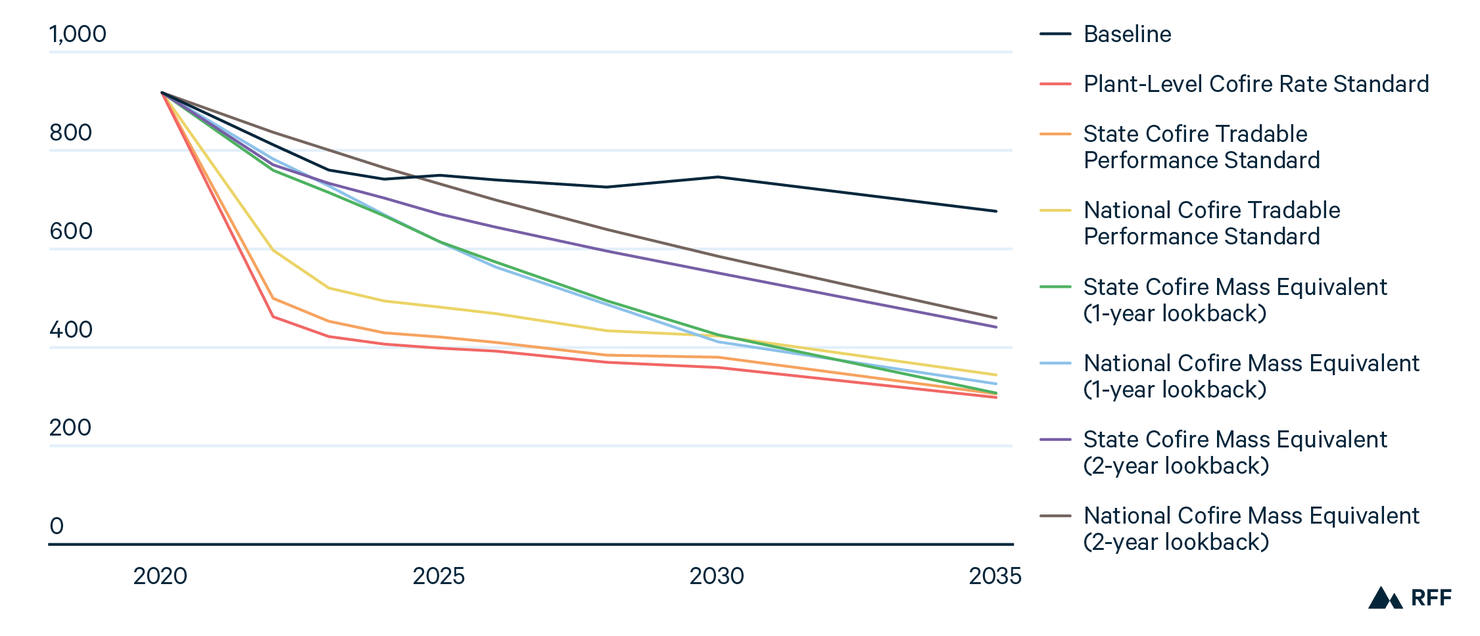

The time profile of emissions from coal plants over 15 years is illustrated in Figure 1 for a 20 percent cofiring standard under the three forms of regulation. For a baseline in Figure 1, we assume no other regulations beyond those in effect at the end of 2020, and other parameters, such as demand and natural gas prices, match Annual Energy Outlook 2019 forecasts. The cofiring standard is assumed to take effect in 2022.

The plant-specific rate-based standard, which is the least flexible approach, achieves the greatest emissions reductions, as illustrated by the bottom curve in the figure. Increased flexibility provided by a tradable performance standard at the state or national level leads to somewhat greater emissions. A mass-based standard at the state and national level falls farther up the continuum of flexibility and results in yet fewer emissions reductions. Figure 1 demonstrates that all forms of the cofiring regulation reduce emissions from coal plants, and the least flexible policies reduce coal emissions the most. Consequently, EPA may want to consider the method of implementation allowed for states in determining the stringency of the standard.

Figure 1. CO2 Emissions at Coal Plants under 20% Cofiring With No Other Regulation (million tons)

2. Adding a cofiring standard to other national electricity policies accelerates emissions reductions.

In the coming years, Congress is likely to create policies designed to decarbonize the electricity sector. We examine how three such policies—a production tax credit for wind and solar, a clean energy standard, and a clean energy standard with banking—interact with a cofiring performance standard at coal plants. The clean energy standard we model requires 80 percent of electricity consumption to be generated with carbon-free electricity by 2032 and includes partial crediting for natural gas plants with emissions rates below 0.44 tons/MWh. All emissions are reported in short tons.

Adding the cofiring standard to each policy moves emissions reductions forward in time and increases cumulative emissions reductions. Figure 2 illustrates results for a plant-specific emissions rate standard. These increased emissions reductions come primarily from the substitution of natural gas for coal, either at coal plants or through reduced utilization of coal plants and expanded use of gas elsewhere. Importantly, compliance with a standalone cofiring standard tends to increase capacity at gas combined-cycle plants; however, combining cofiring with other national policies limits the growth of new gas capacity, pointing instead toward increased utilization of existing gas plants and new renewable facilities. The early emissions reductions achieved when a production tax credit is coupled with a cofiring standard are especially pronounced because the cofiring standard encourages a switch from coal to gas that would not happen under a policy that solely promoted growth in renewables.

Figure 2. C02 Emissions for the Electricity Sector under Policy Combinations with 20% Cofiring Standard (million tons)

3. Cofiring regulations reduce emissions at low cost.

All cofiring policies reduce CO2 emissions at less than $13/ton in our model, and policies with higher flexibility have lower costs but also fewer cumulative emissions reductions (Table 1). The cofiring standard reduces emissions by reducing generation at coal plants as well as increasing cofiring at coal plants. Very little cofiring occurs under the mass-based strategies, but more under the state compliance cases than the national ones. All cofiring scenarios result in an increase in natural gas generating capacity and generation. The more stringent the cofiring policy, the greater the increase. There is no direct correspondence between solar and wind capacity and the stringency of the cofiring policy, although wind capacity is higher in all cofiring cases.

Table 1. Generation Mix at Coal EGUs, Cumulative Emissions Reductions in Electricity Sector, and Cost-Effectiveness under 20% Cofiring Standard (2020$)

4. Low gas prices yield lower emissions in the baseline and under the cofiring standard.

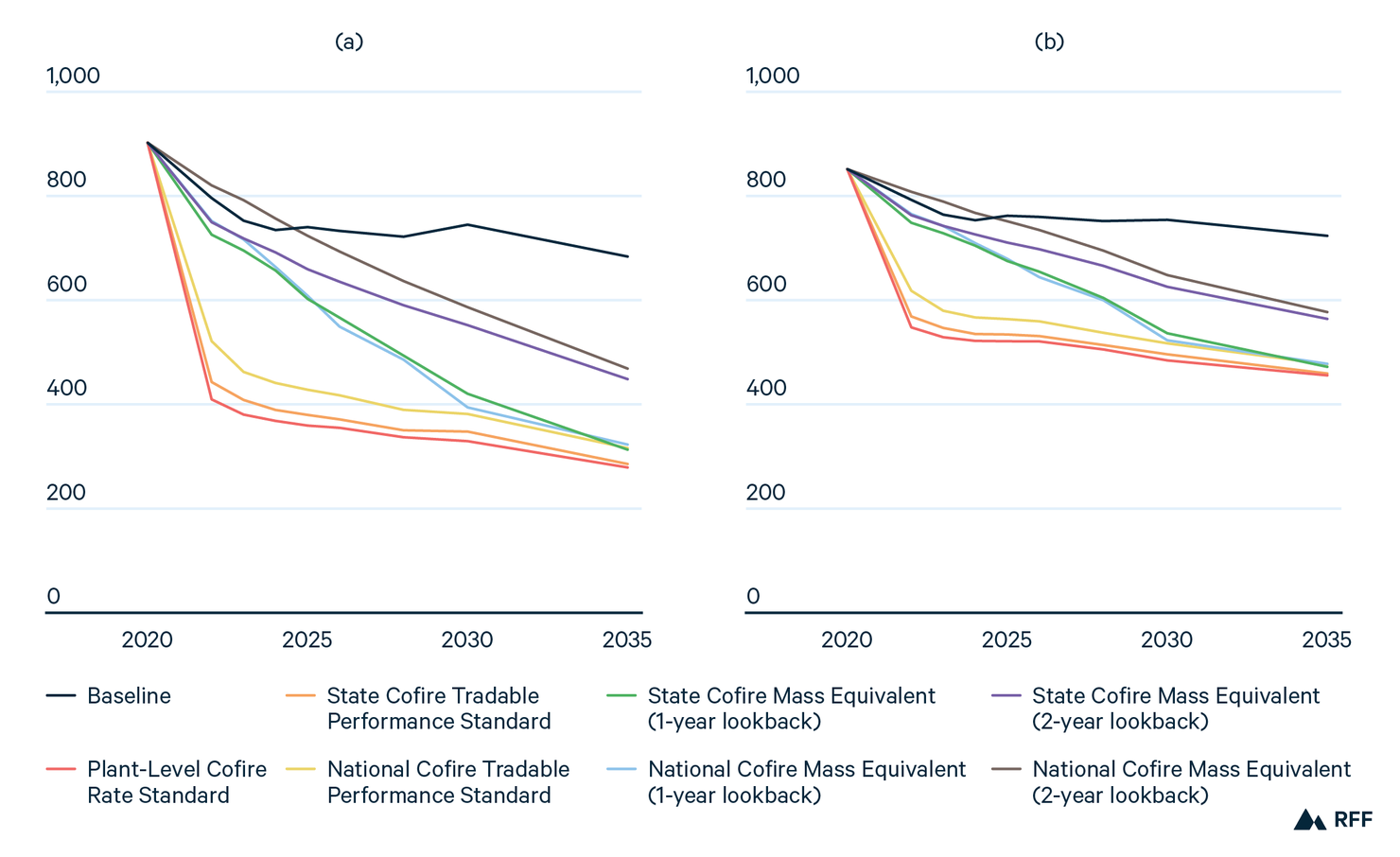

Low natural gas prices yield lower coal generation and higher gas generation in the baseline. Nonetheless, the application of cofiring standards lowers annual emissions relative to that baseline in most cases and by 2030 in all cases (Figure 3, panel a). Compared with the reference case for gas prices, low gas price cases do not have higher rates of cofiring because the levelized cost of energy from a gas plant is still lower than the cost at a coal plant cofiring with gas. Just as in the reference case gas price scenarios, the more flexible the policy, the fewer the emissions reductions and the more emissions reductions are achieved through generation shifting rather than cofiring. Because the mass-based standard ratchets down the emissions budget according to coal plant generation in each year, a coal plant might opt to generate more in early years to maintain the option to continue to generate in later years. We observe this under the national mass-based standards in the low gas price case and the two-year look-back national mass-based standard in the reference gas price case (Figure 1), where coal plant emissions are higher in the early years of the policy than in the gas price reference case.

In further sensitivity analysis, we find that a more stringent cofiring regulation set at a 40 percent standard reduces emissions even more than the 20 percent standard while avoiding the emissions increases in the mass-based scenarios. As before, more flexible implementations lessen emissions reductions (Figure 3, panel b).

Figure 3. CO2 Emissions at Coal Plants under (a) 20% Cofiring Standard and Low Gas Prices and (b) 40% Cofiring Standard (million tons)

5. Health benefits from cofiring policies could be significant. The greater the flexibility of the policy, the greater the uncertainty about the location of benefits.

Coal plants are the primary source of sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions in the electricity sector, and sulfates are primary drivers of negative health outcomes. By reducing coal use and shifting generation away from coal plants, a cofiring standard at coal plants could significantly reduce SO2 in the electricity sector and deliver important health benefits. The location of these health benefits is uncertain and depends on the design of the cofiring standard. Under a plant-level rate-based standard, most coal plants will reduce the amount of coal they burn, but it is possible that some coal plants might increase their total generation even as their emissions rates decrease. Tradable performance standards or mass-based standards increase uncertainty about the location of the health benefits associated with reduced use of coal, since not every coal plant is required to reduce its emissions rate or coal use. In addition, an increase in gas generation under any scenario may create local health harms if increased utilization of gas plants raises local NOX concentrations. Nevertheless, total SO2 and NOX from the electricity sector decrease under a cofiring standard (Figure 4), yielding substantial net health benefits for the United States.

Figure 4. (a) SO2 and (b) NOX Emissions at Coal and Gas Plants under 20% Cofiring Standard (thousand tons)

Conclusion

Existing executive authority under the Clean Air Act is just one of the tools that the Biden administration could attempt to exercise to lower greenhouse gas emissions. Cofiring regulation at coal plants under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act follows an established legal pathway for emissions regulation and can provide significant GHG emissions reductions at coal plants and for the electricity sector at low cost. Cofiring regulations complement potential national electricity policies, such as production tax credits for renewables or a clean electricity standard, by bringing emissions reductions forward in time. The more flexible the design of the cofiring standard, the fewer the emissions reductions, so flexible implementations could be combined with more stringent standards. Cofiring standards offer substantial emissions reductions even with low natural gas prices, and a standard requiring greater levels of cofiring could achieve greater emissions reductions. Cofiring standards will also yield significant reductions in criteria air pollutants, although the location of the reductions will depend on the implementation of the program.