Hydrogen Hubs: Is There a Recipe for Success?

In this issue brief, RFF researchers offer comments on the Department of Energy’s outline of a new clean hydrogen hubs program.

1. Goals and Objectives

In 2022, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) issued a request for information on the design and implementation of a possible clean hydrogen hubs program as a part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The IIJA has a goal of “accelerating research, development, demonstration, and deployment of hydrogen from clean energy sources,” primarily by allocating 8 billion dollars for the development of clean hydrogen hubs (H2Hubs) around the United States. On June 6, after receiving over three hundred responses to a detailed list of questions in its request for information, DOE released a Notice of Intent (NOI) on the implementation of a new H2Hubs program. The NOI alerts all potential bidders to the Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) to come in the Fall.

To get started, under the IIJA, the hubs are to:

- “Demonstrably aid achievement of the clean hydrogen production standard developed under section 822(a) [of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (42 USC 16166a)];

- Demonstrate the production, processing, delivery, storage, and end use of clean hydrogen; and

- Can be developed into a national clean hydrogen network to facilitate a clean hydrogen economy.”

The first point is a requirement for every funded hub to meet the minimum clean hydrogen production standard: Less than 2kg of CO2e emissions per kilogram of hydrogen produced at the site of production. The second point concerns the development of a full clean hydrogen value chain within the H2Hubs. The last point is more vague, since neither the NOI nor the IIJA seems to detail the meaning of a “national clean hydrogen network.” A few possible definitions exist for this network:

- A physical network linking the various hubs;

- Hubs that learn from one another about technologies and best practices

- Economic, environmental and social impacts that are optimized at a national scale rather than at an individual hub level; and

- The establishment of a mature national clean hydrogen market with sufficient producers and end-users and stable prices competitive with carbon intensive hydrogen and substitute fossil fuels. It would be useful for DOE to clarify this term, perhaps in the Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) and/or the expected national clean hydrogen strategy and roadmap.

However these objectives are defined, this program faces a daunting task. Achieving these goals will require dramatic reductions in the cost of creating low greenhouse gas (GHG) hydrogen and the generation of enough demand to buy the production at a price necessary to cover costs and a reasonable profit, irrespective of the subsidies provided by the H2Hubs program. Production will need to be large to take advantage of economies of scale. New technologies on the supply and demand sides will be needed to aid achievement of the clean hydrogen standard and reach the Hydrogen shot goal of decreasing the cost of clean hydrogen production to $1 per kg in a decade. In addition, the applicants must navigate multiple requirements involving production inputs, specific targeted end-uses, varied locations, as well as environmental justice considerations and jobs growth, all under timeline and budget constraints. On the latter constraint, the risk of having an unsuccessful hub has to be low enough to attract at least 50 percent of the financing from private sources.

In this issue brief, we offer our comments on the DOE’s outline of the H2Hubs program.

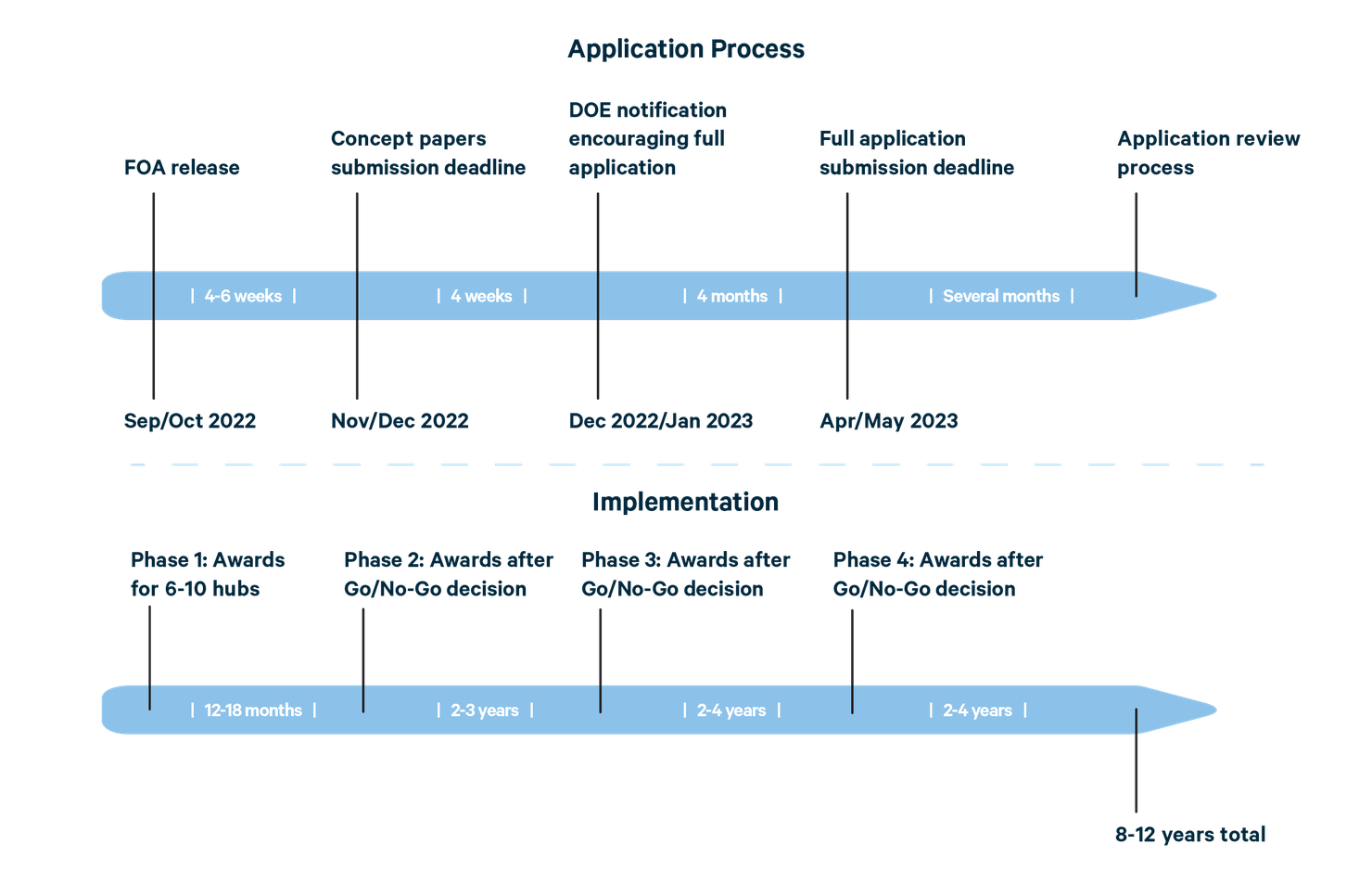

Figure 1. Timeline of the Application Process and Implementation of the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hub Program

2. Timeline of the Program

Figure 1 presents our rendering of the steps in the program. The DOE released its NOI on June 6 signaling to potential applicants that they should assemble their teams and start working on their hub planning and on the associated deliverables expected for the selection process. According to the NOI, the formal Funding Opportunity Announcement should be released in September or October 2022.

As with other large DOE programs, potential applicants are expected to submit a concept paper describing their project, the overall operation of the hub and the associated financing plan. After a review period, the DOE will encourage or discourage potential applicants to submit a full application in April or May 2023. This pre-selection process is a good one, as it limits the private and public resources for hub proposals that do not get over the bar.

After the selection of “six to ten hub projects,” the DOE will negotiate project details with the applicants, such as the nature of the cost-share for each stage. These individual negotiations provide some flexibility to better adapt the hub projects to meet the DOE’s goals while incorporating project particularities in the implementation framework.

Following the selection and negotiations phase, Phase 1 of the implementation process should start “several months” after the full application with one to one and a half years dedicated to the production of a detailed project plan (Figure 2). Phase 2 will focus on the development, permitting and financing plan for the hub. Phase 3 will see the construction of infrastructure and installation of new equipment. And finally, funding in Phase 4 will see the ramping-up of the production and end-use of clean hydrogen within a hub. The releasing of funds for each phase is conditional on an approval process that, as mentioned above, can be tailored for each project during the negotiations period.

The multiple phases approach decreases the risk of failure of the program and perhaps helps de-risk the projects for outside financing, with the DOE holding teams accountable to their goals for each budget period as the funding will be released conditionally on successfully reaching previously set criteria. However, it is crucial that the approval metrics are set beforehand so that both the H2Hubs team and the DOE can commit to it.

3. IIJA Hub Requirements

The IIJA details hub requirements that projects must follow to be considered for funding by the DOE. Overall, hubs selected by the DOE should present feedstock diversity, end-use diversity, geographic diversity and employment opportunities. With this program, Congress wants to demonstrate the production and use of hydrogen in multiple settings. Table 1 shows the characteristics that proposals selected by the DOE have to feature. At least one hydrogen hub shall demonstrate the production of clean hydrogen for each type of feedstock in column 1 and at least one hydrogen hub shall demonstrate the end-use of clean hydrogen in each of the sectors in column 2. In addition, H2Hubs should be located in different regions where they should use local abundant resources, and at least two of them should be located in natural gas abundant regions. Finally, the DOE shall prefer H2Hubs that are likely to create the largest number of local employment opportunities.

Since a hub can produce hydrogen from multiple feedstocks and demonstrate several end-uses at the same time, this leaves us with twelve possible combinations, some of which might not be economically sound. For instance, having a hub based on residential and commercial hydrogen use (blended with natural gas) seems challenging. As the NOI notes that not all the 8 billion dollars will be dispensed through this process, we speculate that the DOE is holding back some of the funding to encourage hub proposals that Congress wanted but the DOE did not receive.

4. Metrics

Besides the legal requirements incorporated in the IIJA, the DOE will give preference to applications that reduce GHG emissions across the full project lifecycle and to H2Hubs that will produce larger quantities of clean hydrogen. In addition, the FOA will incorporate “a range of equity considerations including energy and environmental justice, labor and community engagement, consent-based siting, quality jobs, and inclusive workforce development.” Given the large number of objectives, the DOE might need to better specify where they are willing to be more flexible and which items they will be prioritizing.

The metrics above—GHG emissions across the lifecycle and larger quantities of clean hydrogen—while useful, seem to miss the mark a bit. After all, clean hydrogen is not desirable for its own sake, but as a method for reducing GHG emissions. And while tracking that lifecycle GHG reductions are taking place is certainly desirable, it would be an improvement to count the actual lifecycle reductions and give preference to hubs that promise the most reductions from scope 1 to 3 (Figure 3). It is also important to recognize that lifecycle emissions will change over time as upstream activities become less carbon intensive. Both the present level of lifecycle emissions and prospective future levels (for example, with a low or zero-carbon electric grid) should be taken into consideration when evaluating proposals.

GHG emissions attributed to a company can be classified in one of three categories enabling exhaustive reporting. Scope 1 emissions are directly emitted by the company’s own production site(s) and resource(s) (e.g. GHG emitted by the company’s assets). Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions attributed to energy purchased and consumed by the reporting company (e.g. electricity purchased). Finally, Scope 3 emissions are indirect and come from all the other activities in the company value chain (e.g. GHG emitted during the production of intermediary goods, transportation and extraction of raw materials, distribution of product goods, etc.). It should be noted that, while emissions accounting is pretty much straightforward for Scope 1 and 2, Scope 3 emissions inventory is difficult and requires an extensive amount of good quality data and avoiding double counting. However, full reporting of Scope 1 to 3 emissions provides companies with a better command over their value chain impacts and helps create emissions reductions strategies on a larger scale (GHG protocol, 2011).

In addition, if the clean hydrogen standard is a minimum qualifying level, then proposals that perform better should be given a higher preference for being selected or moving on to the next funding phase.

Relatedly, there is no mention of cost-effectiveness as a preferential metric. If these projects are going to succeed as an economy-wide GHG reduction strategy, their costs per GHG reduction should be targeted, not just hydrogen production costs. Meeting the cost-effective hydrogen production goal is only half – or even less than half – the story, as costs of its distribution and use must also be taken into account.

The use of any metric involving GHG reductions raises the issue of measuring them. Indeed, there exists several accounting methods to summing embodied CO2e emissions over the lifecycle. Thus, a harmonized measurement methodology is called for to enable proper comparison between H2Hubs projects. The DOE defining common system boundaries, emission factors and product allocations to be used seems to be an important prerequisite to ensuring a level playing field and should be made available to applicants in a set of official guidelines. The DOE could leverage the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) expertise on the topic.

5. Lifecycle Impacts

The development of clean hydrogen hubs will have many impacts on energy markets, industries, employment, GHG emissions, environment and communities but also on a broader scale. The DOE “envision[s] that each H2Hub will quantitively estimate and measure lifecycle social and environmental impacts of the H2Hub on the region.” According to the NOI, this lifecycle analysis will likely be in the deliverables required in the initial application.

We agree that measuring the environmental and social impacts of the proposed projects will be useful for the review and selection process and, more generally, for the reporting and monitoring of performances. However, lifecycle assessment is a complex and data intensive exercise. A good assessment means defining the goal and scope of the study clearly; compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and environmental releases; evaluating the potential environmental impacts; and interpreting the results to help decision-makers make a more informed decision (EPA, 2022).

Data collection, environmental and economic impact assessment modeling, and interpretation of the results are key issues. To use lifecycle assessment to facilitate the DOE to make meaningful comparisons among proposed hub projects, we suggest that the DOE be clear on the assessment scope and standardize dataset and assessment models, so the assessment outcomes can be compared among different proposals and interpretation of results can be meaningful and transparent.

Applicants and reviewers should be especially careful about upstream methane leakage in hydrogen production using natural gas as methane’s global warming potential is much higher than CO2. The analysis should also consider hydrogen emissions and potential leakages throughout the value chain, as hydrogen is itself a powerful indirect greenhouse gas. The leakage risks are especially high when using infrastructure designed for natural gas, such as pipelines, since hydrogen is a much smaller molecule (Ocko and Hamburg, 2022).

6. Sustainability and Clean Hydrogen Economy

Under any definition of a clean hydrogen network, the aggregate benefits of the hubs need to be greater than the sum of the benefits of each hub. Indeed, while hubs might be successful individually, they may not succeed in creating the basis of a clean hydrogen network facilitating a nationwide clean hydrogen economy. Thus, the DOE should consider systems integration of these individual hydrogen hubs to optimize the goals of a national clean hydrogen economy, as well as the broader set of metrics discussed above.

For clean hydrogen to be a successful economy-wide decarbonization approach, the “effective” price of substituting clean hydrogen for grey hydrogen, fossil-derived electricity and fossil fuels needs to be competitive. We use the term effective to recognize that regulations may narrow the gap between the price of clean hydrogen and its alternatives, even if the regulations are not price based. Particular regulatory efforts could be both carrots, such as a hydrogen tax credit and 45Q for use in subsidizing blue hydrogen production, or sticks, such as a carbon tax or carbon intensity standard with a fee for degree of violation, as proposed in Senator Whitehouse’s Clean Competition Act.

Implicit in the above point is that even if hydrogen hubs increase their supply of hydrogen to reach the DOE’s goal of $1 per kilogram of clean hydrogen in a decade, the demand might not increase at the same time without targeted support. A sustainable national hydrogen economy may benefit from demand-side policies to balance supply and demand of clean hydrogen. These could include contract for differences for clean hydrogen or government green procurement programs requiring low-carbon content materials or products. More public and private investments in technology R&D and project demonstrations are needed to speed up technology adoptions, such as for fuel cells, green steel and cement, and other demand-side technologies.

7. Environmental Justice Considerations

The Biden Administration has previously emphasized its commitment to tackling the climate crisis and related environmental justice issues. This H2Hubs program includes equity and justice considerations in the selection process. The NOI notes that “the impacts of proposed H2Hubs should be evaluated early in the planning process and information about the effects, costs and benefits should be provided to stakeholders in advance of community engagement.” Additionally, it suggests that applicants use Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs) or other similar partnerships including local communities in the decisionmaking process.

While CBAs have served as important tools in the development process in many instances, several criticisms from environmental justice advocates have emerged. The most significant criticism centers on the idea that CBAs, on their own, lack a mechanism to ensure their representation of community needs and desires, especially when representing low-income workers and residents or communities of color. It is important for these community groups to understand how CBAs might protect their interests in the development process (De Barbieri, 2017).

8. Conclusion

Overall, this NOI presents a reasonably tasty appetizer. Multiple funding phases that break down this long-term program into smaller action items enable better monitoring on the DOE’s side and achievable goals on the applicants’ side. Giving preferences to proposals that achieve GHG emissions reductions across the full lifecycle and produce larger amounts of hydrogen seems sound considering the overarching goal of facilitating a clean hydrogen economy to support the Biden Administration’s decarbonization goals.

However, the DOE should keep in mind that with many requirements and objectives, tradeoffs are inherent. Achieving national decarbonization goals would require going one step further and giving preference to hubs that can attain the largest GHG emissions reductions across their full lifecycle. The definition and the weight given to each metric (e.g. GHG emissions, cost-effectiveness) are also crucial to a successful program. DOE should consider additional support policies on the hydrogen supply and demand side to help ensure the program’s success.