US Electricity Markets 101

An overview of the different types of US electricity markets, how they are regulated, and implications for the future given ongoing changes in the electricity sector.

In the United States, how electricity is bought and sold varies by region. While many cities are served by municipally owned utilities and some rural areas are served by customer-owned rural cooperatives, most electricity customers are served by utilities that are owned by investors. These investor-owned electric utilities can be either regulated and operate as vertically integrated monopolies with oversight from public utility commissions, or they can operate in deregulated markets where electric energy prices are set by the market with some federal oversight of wholesale market operations. These regulatory constructs determine how retail and wholesale electricity prices are set and how power plants are procured. This explainer discusses the different types of US electricity markets, how they are regulated, and implications for the future given ongoing changes in the electricity sector.

For definitions of bolded terms and other concepts related to the electricity grid and industry, check out “Electricity 101.”

Traditional Regulated Markets

Prior to the 1990s, most investor-owned electric utilities were regulated and vertically integrated, which means the utilities owned electricity generators and power lines (distribution and transmission lines). Today, only one third of US electricity demand is serviced by these integrated utility markets because many states have abandoned this system in favor of deregulation.

Utilities in traditionally regulated regions operate as a monopoly in their territories, which means that customers only have the option to buy power from them. To keep electricity rates reasonable for customers, state regulators oversee how these electric utilities set electricity prices. Retail electricity prices in these areas are set based on recovering the utility’s operating and investment costs alongside a “fair” rate of return on those investments (collectively called a revenue requirement). This revenue requirement must be approved by the state’s public utilities commission, which prevents utilities from overcharging customers for electricity.

Regulated utilities must also seek state approval for power plant investments. Vertically integrated utilities decide which generators to build and then recover the costs of these investments through electricity rates. Many state regulators require utilities to demonstrate the necessity of proposed investments through an integrated resource planning (IRP) process. This process is used for long-term planning and requires each utility to justify its investment and demonstrate how it plans to meet customer electricity demand. Notably, under this structure, customers bear the risk of investments because utilities can recover their costs through rates, regardless of how the power plant performs (for example, South Carolina electricity customers paid for nuclear plants that were never constructed).

Even though vertically integrated utilities generate their own electricity, many trade with other utilities during times of need. For example, during certain times of the year it may be cheaper for some utilities to purchase excess hydroelectric power from others rather than generate power using their own facilities. This type of wholesale bilateral trading is especially common in the western and southeastern United States where most utilities are still regulated. These wholesale market transactions are subject to regulation by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Deregulated Markets

Beginning in the 1990s, many US states decided to deregulate their electricity systems to create competition and lower costs. This transition, known as restructuring, required electric utilities to sell their generating assets and led to the creation of independent energy suppliers that owned generators. Because each new independent energy supplier could not cost-effectively create their own power line infrastructure, electric utilities held onto these assets and became transmission and distribution utilities, which continue to be regulated.

The biggest impacts resulting from deregulation were changes to retail and wholesale electricity sales, with the creation of retail customer choice and wholesale markets.

Retail Deregulation: Customer Choice

In deregulated areas, electricity customers have the option of selecting an electric supplier (known as customer choice) rather than being required to purchase electricity from their local electric utility. This introduces competition for retail electricity prices. Since many electric suppliers can exist within a region with customer choice, electric retailers offer competitive prices to acquire customers. For customers who choose not to select an independent power supplier, their local utility is still obligated to provide them with electricity that the utility will purchase from generators.

For consumers, there are pros and cons to selecting a supplier other than their local utility company. Retail competition can help lower a customer’s electric bill and allow them to tailor their energy use to their preferences, such as by selecting a clean energy supplier. However, independent companies often require customers to sign contracts, which can lock them into a set electricity price for multiple years (Contracts with generation suppliers typically offer the customer a fixed charge—dollars per kilowatt-hour of power—over a certain amount of time). While fixed rates could be beneficial for some customers, they could also negatively impact others if the rate they agree to ends up being more expensive than the rate set by the local utility. Also, it is important to note that customer choice is only applicable for the generation portion of a customer’s utility bill because transmission and distribution services are still provided by the local utility company, since these services are a natural monopoly (as discussed above). Consequently, only a portion of electric rates in these areas are set competitively.

Wholesale Deregulation: Creation of Competitive Wholesale Markets

Unlike regulated states that plan for investment, deregulated states use markets to determine which power plants are necessary for electricity generation. As utilities and competitive retailers in deregulated regions do not generate their own electricity, they must acquire power elsewhere for their customers. Centralized wholesale markets—in which generators sell power and load-serving entities purchase it and sell it to consumers—provide an economically efficient method of doing so (discussed more in the next section). Notably, under this structure, investment risk in power plants falls to the electric suppliers and not to customers, unlike in regulated markets.

Following deregulation, regional transmission organizations (RTOs) replaced utilities as grid operators and became the operators of wholesale markets for electricity. These RTOs have evolved over time.

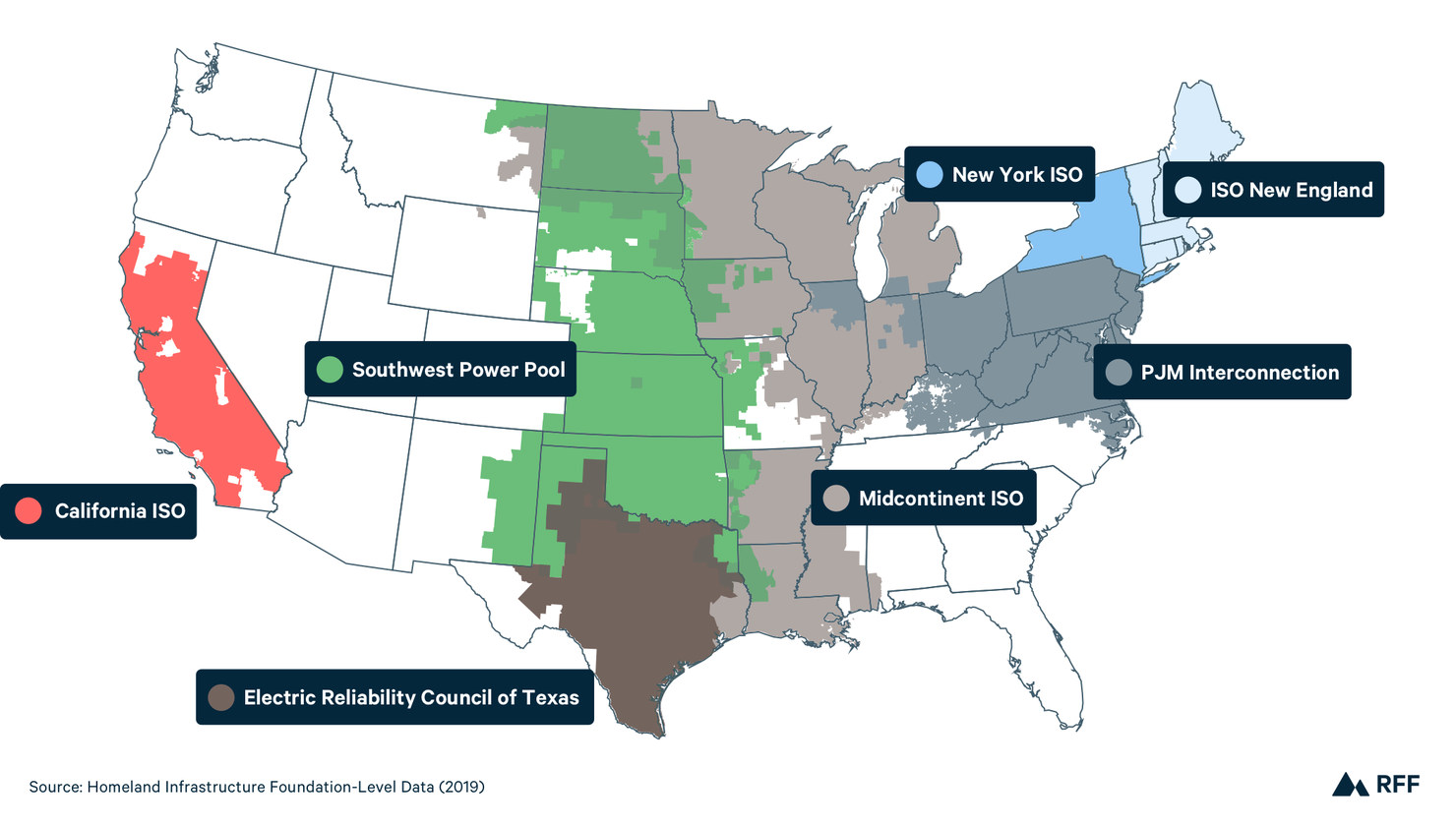

Regional Transmission Organization Map

Since many RTOs operate wholesale markets that encompass multiple states, they are regulated by FERC (with the exception of the Texas RTO, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas—or ERCOT). FERC has oversight of all wholesale power transactions on the two large, interconnected grids: the eastern and western interconnects.

While regulated utilities base retail rates on a regulated rate of return on investments (as described above), deregulated retail utilities purchase electricity at market-determined wholesale prices and then sell that electricity to customers at market-determined retail prices, given competition from other retailers. RTOs typically run three kinds of markets that determine wholesale prices for these services: energy markets, capacity markets, and ancillary services markets.

Energy Markets

Energy markets are auctions that are used to coordinate the production of electricity on a day-to-day basis. In an energy market, electric suppliers offer to sell the electricity that their power plants generate for a particular bid price, while load-serving entities (the demand side) bid for that electricity to meet their customers’ energy demand. Supply side quantities and bids are ordered in ascending order of offer price. The market “clears” when the amount of electricity offered matches the amount demanded, and generators receive this market price per megawatt hour of power generated.

RTOs typically run two energy markets: the day-ahead and real-time markets. The day-ahead market, which represents about 95 percent of energy transactions, is based on forecasted load for the next day and typically occurs the prior morning in order to allow generators time to prepare for operation. The remaining energy market transactions take place in the real-time market, which is typically run once every hour and once every five minutes to account for real-time load changes that must be balanced at all times with supply.

RTOs use energy markets to decide which units to dispatch, or run, and in what order. In the day-ahead market, RTOs compile the list of generators available for next-day dispatch and order them from least expensive to most expensive to operate. For example, since wind plants operate without fuel, they are able to bid $0 into the energy market and get dispatched first. Dispatching units by lowest cost allows the market to meet energy demand at the lowest possible price. During periods of high demand, wholesale prices rise accordingly because more high-cost units need to be dispatched to meet electric load.

Base wholesale market prices typically reflect the price for power when it can flow freely without transmission constraints across the RTO’s territory. When that is not possible, RTOs account for congestion on transmission lines by allowing prices to differ by location. As a result, areas with high demand and scarce electric resources typically have higher prices than those with abundant generation relative to load.

Capacity Markets

Electricity retailers are required by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), an independent organization that ensures grid reliability, to support enough generating capacity to meet forecasted load plus a reserve margin to maintain grid reliability. Some RTOs run a capacity auction to provide retailers with a way to procure their capacity requirements while also enabling generators to recover fixed costs, i.e., costs that do not vary with electricity production, that may not be covered in the energy markets alone.

The capacity market auction works as follows: generators set their bid price at an amount equal to the cost of keeping their plant available to operate if needed. Similar to the energy market, these bids are arranged from lowest to highest. Once the bids reach the required quantity that all the retailers collectively must acquire to meet expected peak demand plus a reserve margin, the market “clears”, or supply meets demand. At this point, generators that “cleared” the market, or were chosen to provide capacity, all receive the same clearing price which is determined by the bid price of the last generator used to meet demand.

Payments to generators in the capacity market are essentially a reward for that generator being available to operate and provide electricity if needed. Consequently, if generators are unavailable to operate during a time when they are called upon, they may face fees under capacity performance requirements.

Ancillary Services Market

RTOs use the ancillary services market to reward other attributes that are not covered in the energy or capacity markets. Ancillary services typically include functions that help maintain grid frequency and provide short-term backup power if a generating unit stops.

Variation Across Regions

Not all states fall neatly into one of these categories. Participation in RTOs and wholesale markets does not require retail customer choice or for local utilities to sell their power generation assets, and many states have chosen to embrace certain aspects of deregulation while maintaining some parts of regulation.

Some regulated states with vertically integrated utilities still join an RTO for grid services. In West Virginia, for example, utilities are rate-regulated and own their own generation, but the state still participates in wholesale markets in PJM, the mid-Atlantic RTO.

Some states have deregulated their wholesale markets but not retail markets. California, for example, is partially deregulated and formed its own RTO, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO), which operates the grid and wholesale markets. However, the state does not offer individual customer retail electricity choice, although communities can opt out of the local utility through community choice aggregation under which a company hired by the community buys power in wholesale markets for all residents who do not opt out of this arrangement.

The structure of wholesale markets varies across regions as well. For example, ERCOT, the RTO of Texas, does not run a capacity market and instead relies on price signals in the energy market alone to ensure reliability. High prices in the energy market, typically caused by low supply and high demand, provide an economic signal for more generators to enter the market, which can then lower energy prices and provide a signal that enough generating capacity is available to meet demand. However, when generators cannot meet demand—such as during the large winter storm that hit Texas in February 2021—electricity services can fail, leaving customers in the dark or paying exorbitant fees. CAISO similarly does not run a capacity market and relies on retailers to ensure resource adequacy to meet NERC reliability requirements.

The Future of Electricity Markets

Many states have policies in place that promote a long-term transition to cleaner renewable sources of energy, like wind and solar power. As renewable generators become a larger portion of the grid’s resources, complications may arise with the existing wholesale market structure in deregulated states. Renewable energy sources do not require fuel inputs to run since they use energy from the sun, wind, and other natural sources. Consequently, they can offer bids of $0 into the energy and capacity markets. As these sources make up a larger portion of the grid over time, these $0 bids can significantly reduce wholesale prices for energy and capacity and could discourage long-term investment for all resources. As a result, wholesale markets may need to adapt in the future to better accommodate different types of resources.

For more detailed information on all of the above, see FERC’s Energy Primer.