Transmission 102: Building New Transmission Lines

This explainer reviews the actors involved in transmission expansion and the barriers involved in constructing new lines.

As the electricity grid continues to evolve, new transmission lines that deliver power from power plants to electricity distribution networks will be needed to connect new generation and serve growing demand. In Transmission 101, we discussed how regional transmission organizations (RTOs), utilities, and other agencies plan for transmission needs.

However, even when the need for transmission expansion is clear, the process of building transmission lines is complicated by line ownership, siting and permitting lines, and cost allocation across regions. This explainer offers background on the actors involved in building transmission and the complex policy landscape that can obstruct investment in new infrastructure.

Who builds new transmission?

Historically, all electricity services in the United States were offered by “vertically integrated” utilities. These utilities owned generators, transmission lines, distribution lines, and interaction with retail customers. With the wave of market deregulation in the 1990s, some regions allowed these functions to be broken up so that generation companies were independent from distribution companies (see Electricity Markets 101 explainer for details). At the time, many competitive market enthusiasts thought there was an opportunity for transmission lines to also be separated from regulated utilities, where companies could own and compete for opportunities to build new transmission lines across regions and charge for services on their lines. Today, most transmission lines are still owned, operated, and proposed by regulated utilities, with a few exceptions. Defined below are the three main types of transmission ownership.

- Utility-owned transmission: Utility-owned transmission connects new generation sources and relieves congestion on existing lines. Utilities assess what transmission investment is needed, propose the line to the RTO or the state’s public utility commission, and then receive a fixed rate of return once approved. Utilities sometimes have a “right of first refusal” on new lines, which prevents other companies from being able to own competing transmission lines. Many argue that right of first refusal laws hinder competition between transmission providers, which would encourage cost reductions and greater efficiencies, but it may also create less resistance to new lines from incumbent utilities. Most transmission in the United States is owned by utilities.

- Merchant transmission: Merchant transmission refers to a class of transmission development that is not prompted by RTOs and does not require a fixed rate of return to the utility owner. Developers may site and build a line without a guaranteed payment, instead charging load-serving entities (LSEs) for using the lines, hoping to recoup their costs. Merchant lines are uncommon because projects can face challenges finding enough customers to make their projects profitable. LSEs that would buy capacity on merchant lines are often associated with utilities that own and operate their own transmission lines. Merchant transmission in the mid-Atlantic PJM grid, like the Neptune line, makes up less than 1 percent of total transmission capacity in the RTO’s footprint.

- Transmission companies: One last model for transmission ownership is independent transmission companies. Rather than different lines being owned by different utilities, transmission companies are independent transmission owners and operators that own all the transmission in the region. This model reduces competition between utilities and streamlines transmission ownership. It still relies on the fixed rate of return model used by utilities, since it is also a natural monopoly market. Vermont Transco LLC is an example of a state-wide transmission company. Vermont’s municipal and cooperative utilities have shared ownership of the Vermont Electric Power Company (VELCO) proportionate to their load ratio. When VELCO makes new investments, each shareholder invests a proportionate amount based on its load ratio and receives the fixed rate of return.

Who pays for transmission?

Most transmission lines owned by utilities are compensated at a fixed rate of return based on their investment by ratepayers. Transmission owners charge fees for using their lines based on federally approved rates. In PJM, the main transmission rate is referred to as Network Integration Transmission Service (NITS) rates, which vary by utility.

Responsibility for line costs is allocated among transmission regions based on cost allocation formulas. FERC Order 1000 established six principles for cost allocation:

- Costs must be “roughly commensurate” with estimated benefits

- Those who do not benefit from transmission should have no cost burden

- Benefit‐to‐cost thresholds must not be so high as to eliminate projects with significant net benefits

- All regions must agree to the allocation of costs in their region

- All cost allocation methodologies must be transparent

- Different transmission facilities may have different considerations for cost allocation.

Projects can be stalled or fail because of fights over cost allocation, particularly when lines are desirable to meet clean energy goals of one region rather than solely to bolster reliability or reduce electricity prices.

What is the process for getting approval for a new transmission line ?

Transmission permitting and siting requires a wide variety of approvals from federal, state, and local agencies, as well as private landowners. The complexity of the approval process depends on the size and scale of the transmission line. For example, a short line that can leverage an existing right of way along a federal highway would be easier to get approval for than an interregional line that crosses federal, state, and private lands in various locations. Once a line crosses through multiple different types of land, the list of necessary approvals and potential challengers grows.

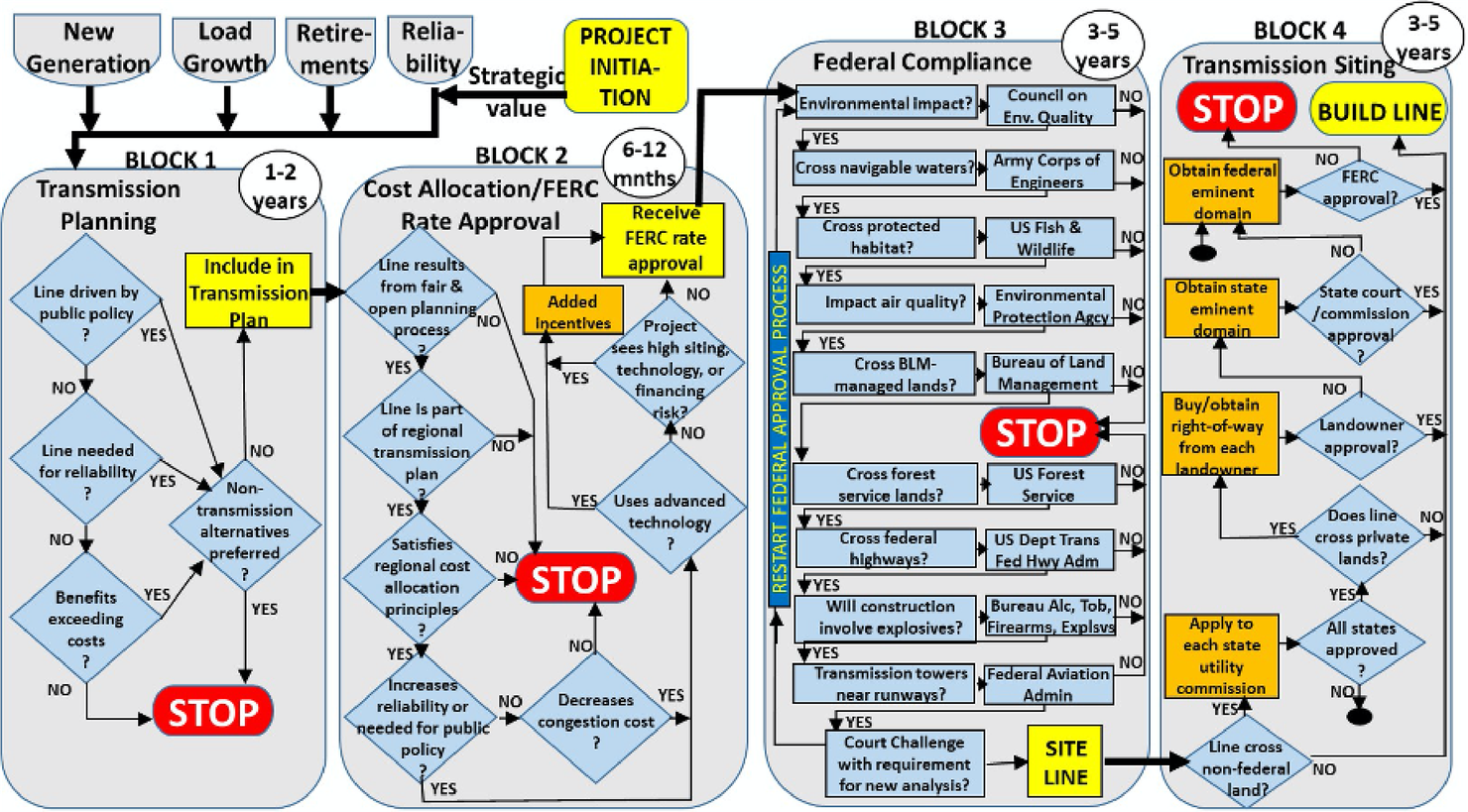

Figure 1 shows a schematic map of the different federal, state, and local approvals processes that may be needed based on the proposed line’s path through federally regulated lands. The Biden administration recently proposed a streamlined process that would funnel these approval processes through the Department of Energy, hoping to shorten the years-long process many developers face. But it is only one piece of the permitting process.

Figure 1. Transmission Approval Processes

Once federal approvals have been achieved, developers must get approval from each relevant state utility commission that the line crosses through, and they must purchase rights of way or get eminent domain rights for all private lands the line intersects. This process can prompt legal challenges from landowners and community groups and can take years to complete.

Impediments to transmission buildout

The lengthy approval process for transmission lines provides interested parties with many opportunities to block transmission projects. These blocks can delay projects by years or prevent them from being built at all. Some key stakeholders have more incentive from others to stop transmission construction:

- Competitive generators that may lose business or face lower market prices for their power if lines were built

- Community stakeholders that don’t want to look at lines or are worried about electromagnetic radiation

- Environmental groups that protect vulnerable habitats and lands that might be disrupted by line construction.

A recent effort to build a transmission line in Maine serves as an example of these dynamics. The 2018 proposal to build a 145-mile-long direct current line to supply up to 1,200 MW of Canadian hydropower to the New England grid is still barely underway. First, during the initial comment period, incumbent generators in Massachusetts claimed that the transmission line would suppress prices and cause the existing natural gas facilities in Maine to retire, leaving the state vulnerable to reliability concerns. Next, environmental groups filed an injunction to secure more rigorous environmental screening from the Army Corps of Engineers, further delaying construction. Finally, a citizen-led ballot initiative to block the line’s construction passed with 60 percent of the vote in November of 2021. After years of delay, line construction started again in 2023, with an estimated 50 percent increase in costs from initial estimates made prior to legal challenges and delays.

Line developers have thought of many ways to minimize these stakeholder challenges, like in New York, where two large transmission lines are being built underground and along existing rights of way to minimize environmental and community challenges. Environmental groups like the Nature Conservancy are also making efforts to optimize infrastructure siting to minimize the impact on vulnerable environmental areas while also maximizing efficiency.

Line developers have also tried to financially compensate regions that are affected by transmission lines but with limited success. Two proposed transmission lines on Cape Cod, Massachusetts connecting offshore wind to the main transmission system would deliver $50 million over 25 years to the impacted municipalities. Despite this compensation and the fact that the lines would be underground, community advocates continue to oppose the line’s construction.

The multifaceted siting and permitting process is designed to provide stakeholders with opportunities to voice their concerns about large infrastructure projects. Reforms to the transmission siting and permitting process are focused on how to balance the need for active community engagement with the demand for a much more robust and capable electrical grid on a tight timeline.

The evolution of transmission policy

The federal and state governments have recognized the challenges associated with the lengthy planning, permitting, and siting process for transmission lines. Several transmission-related policies have been adopted as part of broader efforts to decarbonize the economy. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act updated the process for designating National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors. While these corridors, which identify areas subject to a streamlined permitting and approvals processes for transmission projects, have long been around in theory but no corridors have been designated yet. The Inflation Reduction Act also appropriated almost $2.9 billion for transmission investments, including loans and grants.

Permitting reform more broadly, which would address construction delays for transmission construction and many other different types of infrastructure projects, is also being considered. Multiple proposals have been brought before congress (including one from Senator Joe Manchin, one from Senator Shelley Capito (RESTART), one from Senator John Barrasso (SPUR), and one from Representatives Martin Heinrich and Scott Peters (FASTER). These proposals either create strict timelines for permitting decisions, offer limited windows for litigation challenges, and/or prioritize select projects of national importance to receive. None of these bills have been enacted, but many lawmakers still view permitting reform as a top legislative priority to address decarbonization goals.