Defining the Inflation Reduction Act’s “Energy Communities”—and Finding Room for Improvement

A new study from Resources for the Future offers several interpretations of the Inflation Reduction Act’s provision to encourage clean energy projects in “energy communities”—and details a new approach to better target places that may need new economic development the most.

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022 introduced a slew of incentives to bolster clean energy production in the United States. Many incentives have people buzzing, including one that offers a 10 percent increase in federal tax benefits if a clean energy project is sited within an “energy community.” But how, exactly, is such a community defined?

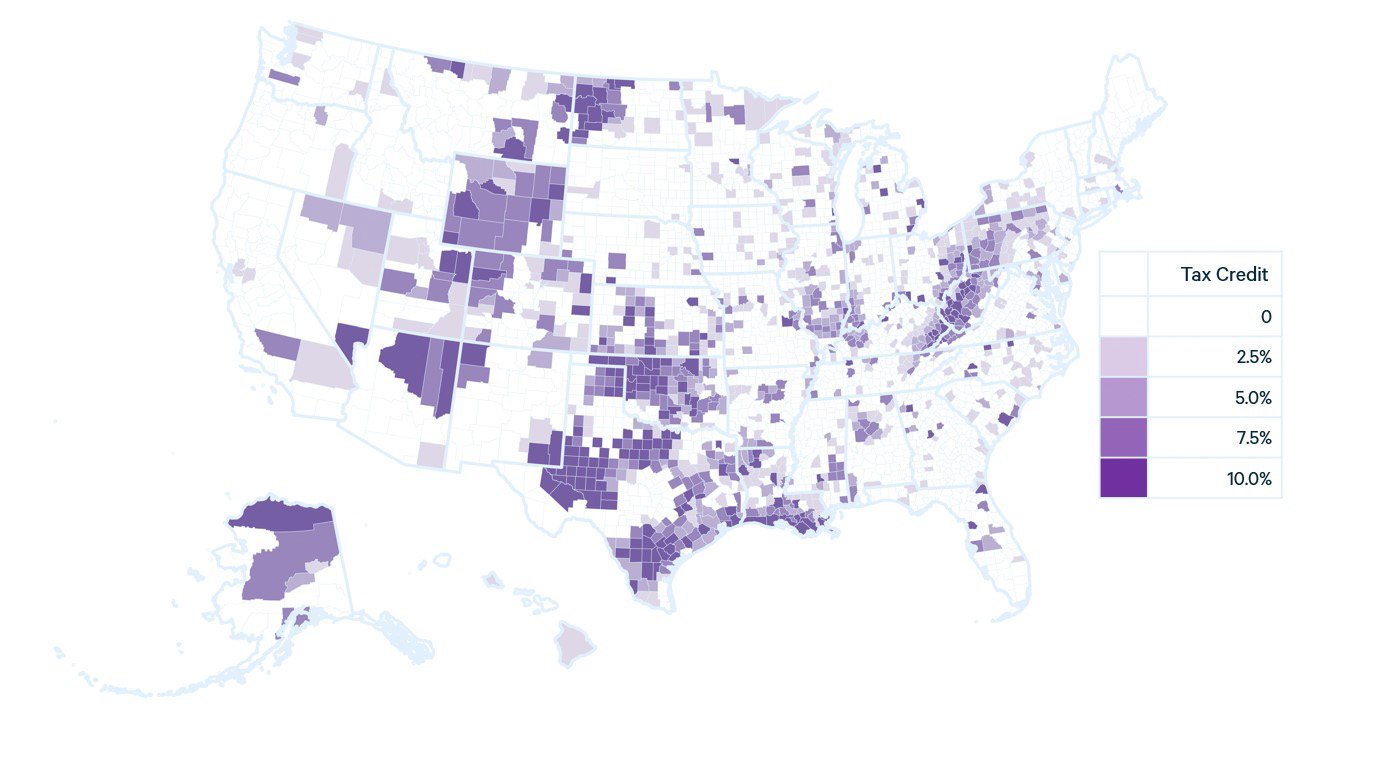

A new paper by scholars at Resources for the Future (RFF) details several interpretations of the energy communities provision, which aims to mitigate the negative economic effects of a decline in fossil fuel activities. The authors find that the Inflation Reduction Act’s definition of “energy communities” covers between 42 to 50 percent of US land area and is unlikely to precisely target communities that will be most heavily affected by the transition away from fossil energy.

Following the publication of their popular Common Resources blog post and sustained interest in this provision, paper coauthors Daniel Raimi and Sophie Pesek mulled over three interpretations of the provision and combed through data sets to map out what areas could be considered energy communities according to the Inflation Reduction Act. While the US Department of the Treasury is ultimately responsible for interpreting and implementing the law, the authors’ work aims to give decisionmakers and companies an idea of scope until an official decision is made. Detailed maps of all three interpretations can be found in the paper.

Raimi and Pesek find that, while the law is likely to channel additional resources to some regions with a high economic dependence on fossil fuels, it will likely exclude many dependent regions as well. Because one stipulation of the provision is that an area must have a higher-than-average unemployment rate to be considered an energy community, large regions with extensive fossil fuel-based industries in states like Louisiana, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Texas are excluded, while large swathes of states where fossil fuels do not play a major role in the economy (such as Maine, Michigan, and Oregon) are included.

“Achieving our climate goals means that fossil fuels will make up less of the energy mix in the coming decades,” said Raimi, a fellow at RFF and director of its Equity in the Energy Transition Initiative. “Even if communities are thriving now under a fossil fuel-based economy, these conditions are likely to change in the future. Ensuring an equitable energy transition means that we need to enhance economic resilience in fossil fuel communities, and that will take time. That includes parts of the country that are struggling today, but also regions where the economy is strong because of coal, oil, and natural gas production. ”

In light of this finding, Raimi and Pesek developed their own definition of an energy community that would more narrowly target fossil fuel-dependent communities. They suggested targeting counties rather than larger geographic areas (which is used in the law), cutting the unemployment requirement, including counties with operational coal-generating units and mines, and more. Importantly, they suggested scaling financial incentives to reflect the level of fossil fuel activity in each county, so that only a portion of energy communities would receive the full 10 percent tax incentive increase. The authors’ methodology resulted in a distribution of energy communities that would cover 39 percent of the United States’ land area, with about 10 percent eligible for the full tax incentive.

“The purpose of developing our own definition is mainly to show that federal resources could be more precisely targeted,” said Pesek, a research analyst at RFF. “Policies can evolve, and it’s important to look at this issue from multiple angles and perspectives to provide some avenues for future policy evolution. Supporting fossil fuel communities as the United States decarbonizes is incredibly important; taking extra care to make sure that decisionmakers approach it with all available options will help ensure that no community gets left behind.”

For more, read the new paper, “What Is an ‘Energy Community’? Alternative Approaches for Geographically Targeted Energy Policy,” by RFF Fellow Daniel Raimi and Research Analyst Sophie Pesek. Check out the related blog post, “What is an ‘Energy Community?’,” which Raimi and Pesek published in early September.

Tune in for our event on November 1 from 1:00 p.m. to 2:00 p.m. EDT to learn more about these findings, and about what the Inflation Reduction Act’s provisions targeting energy communities could mean for fossil fuel-dependent communities.

Resources for the Future (RFF) is an independent, nonprofit research institution in Washington, DC. Its mission is to improve environmental, energy, and natural resource decisions through impartial economic research and policy engagement. RFF is committed to being the most widely trusted source of research insights and policy solutions leading to a healthy environment and a thriving economy.

Unless otherwise stated, the views expressed here are those of the individual authors and may differ from those of other RFF experts, its officers, or its directors. RFF does not take positions on specific legislative proposals.

For more information, please see our media resources page or contact Media Relations and Communications Specialist Annie McDarris.